Best Practices

Progression of Participation

Self-Determination

Developing a student-led IEP program requires hard work, however. Everyone on the team has to be on board—student, parents, teachers, related service providers, and administrators. It can be challenging to make time for this work during a busy school day, and sometimes families have a lot of questions about why their young child should participate. Some of the most common barriers to developing a school-wide vision for student-led IEPs are discussed below.

Making Time to Provide Students with Leadership Opportunities in the IEP Process

School days are busy! Everyone wears multiple hats and juggles competing priorities. Grade these papers? Call that parent? Write next week’s quiz? Maybe you need to make last-minute adjustments to lesson plans? Yet, student-led IEPs are so powerful that committing to the time to prepare is worthwhile.

Budgeting time for the process is the most common and most challenging barrier to overcome. Teachers leading this process must first work with students and their families to identify an appropriate level of participation. Then, teachers must plan age-appropriate and meaningful ways to help students learn to analyze data, craft IEP goals, and make implementation plans. This work can be time-consuming, and it requires thoughtful planning.

The purpose of making time for organization and planning is to make sure the rest of your workflow throughout the month and quarter is as clear and efficient as possible. Try these steps:

Create Designated Planning Times

Set aside time during a planning period at designated intervals, such as once per month or twice per quarter. Get organized about where each student on your caseload is in terms of leadership in the IEP process.

Determine the Family’s Preferred Communication Channel

Plan when and how you will communicate with the student’s family. Do they prefer email? An afterschool phone call? An evening text message?

Stay on Top of Your Master IEP Schedule

Double-check your calendar for upcoming IEP meetings to make sure nothing takes you by surprise.

Prepare Your Paperwork in Advance

Create or update the templates you use during your meetings with students as you craft goals and reflect on progress together. (This way, you only need to tweak resources before a meeting with a student.)

Drill Down to a Monthly Schedule

Make your schedule for the coming month (or quarter) to solidify which students you will meet with and when. If you need to get coverage for a class or check with an administrator, do so during this sacred time.

When Parents Are Reluctant to Include the Student in a Leadership Role

Teachers may find some parents are hesitant about allowing their child to participate in the IEP process. This is normal! As the primary advocates for their children, parents want to ensure the school does what’s best for their children. Of course, teachers want what’s best for a child, too! But some parents may worry that having their child participate in the IEP process will feel overwhelming.

One of the most helpful things teachers can do to reassure parents is to explain that there is a continuum of leadership roles and a progression of participation in the IEP process. Help them understand exactly how their child will be involved and ask for their ideas. It is usually wise for most students to begin with an observational role, or to submit a contribution in writing or by a video prepared beforehand. Dispel the fear that the child will be put on the spot in the middle of the meeting to answer a challenging or accusatory question in a room full of adults.

Above all else, remember that parents are partners in the IEP process and collaboration is essential to a strong, effective IEP team.

Involving Young Children in Their IEP Meetings

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) requires students to be invited to their IEP meetings starting at age 14, or whenever transition planning will be discussed. Many school teams have begun to invite younger students, however. Research shows that children of all ages can benefit from participating in the IEP process, including those in early childhood and elementary school. Some teachers and families may have questions about the best way to engage younger children in the process.

A good place to start with this age group is to help them understand they have a special plan called an IEP that helps them learn at school. Younger children don’t necessarily need to know the name or nature of their disability, but learning to self-advocate starts with a basic awareness of what the IEP is.

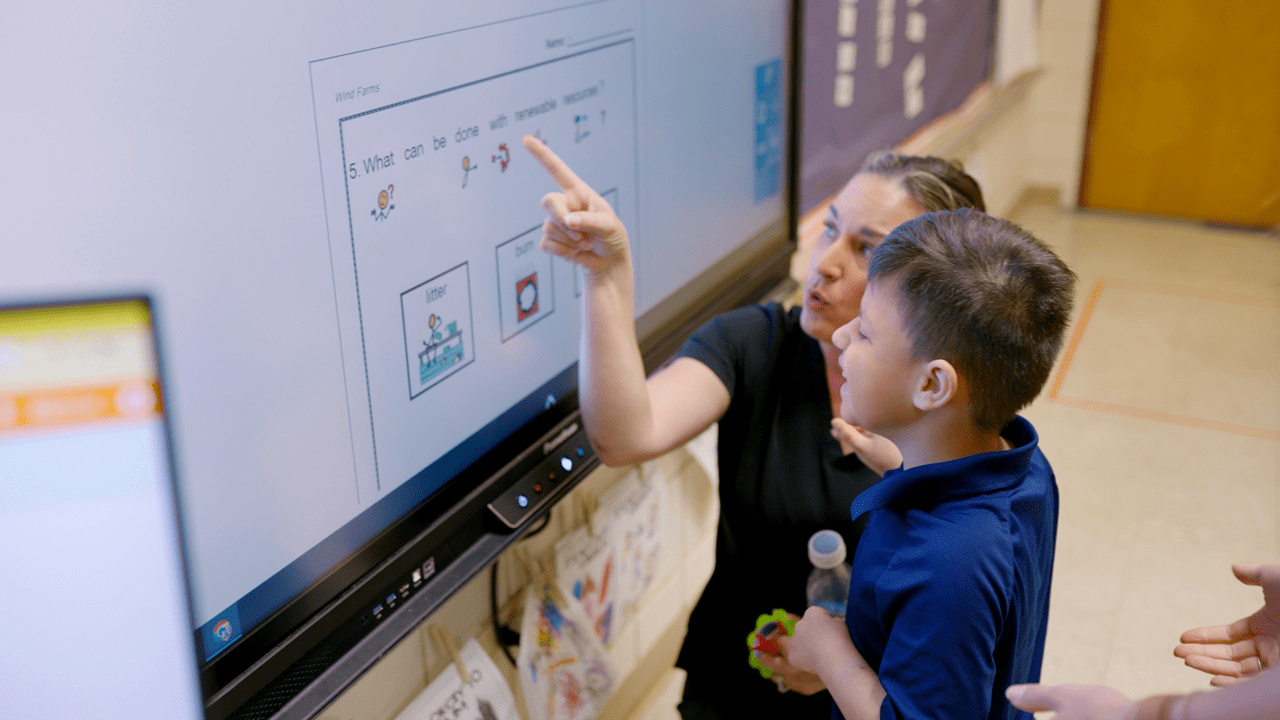

Explain to the child with words or pictures how a team of adults works together with the child to help them succeed at school. If possible, provide one concrete example of how the special learning plan helps. For example, a first-grade student with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) might use fidget toys, noise-canceling headphones, and flexible seating throughout the day. You could explain to them that these special learning tools help them be their best self at school, and their special learning plan makes sure they can use them when they need to.

Another important topic for initial conversations with young students is personal interests. Most students can identify personal likes and dislikes when presented with multiple-choice options, pictures, or sentence starters.

Prompts for Discussion

What do you like to eat for dessert? Point to the foods you like best.

What is your favorite subject in school? Math, science, history, reading, writing, art, music, or PE

My favorite sport is __________.

On the weekends, I like to __________.

The student’s interests need to be shared with the team at the IEP meeting even if they don’t relate directly to their IEP goals. Doing so shows the student that the grownups listen and care about their interests.

It may be possible to link the questions and prompts about likes and dislikes to data and goals that relate to academics and therapeutics in the classroom. This will depend on the individual student’s needs and abilities. Make a concerted effort to make this connection for young kids, as students who see the progress they make become more motivated and self‑aware.

Following Through Within and Across School Years

Following through within and across school years is another challenge in making a vision of school-wide student-led IEPs a reality.

A dedicated, passionate special education teacher or case manager may do wonders with budgeting time, connecting with families, and facilitating the student-led IEP meetings. But what happens after the meeting? The aftermath of the meeting is as important as the preparation leading up to it. The IEP process is a process—meaning it is ongoing. Everyone on the team has a part to play in helping the student follow through with goals and self-advocacy work.

For example, one outcome of an IEP meeting for a middle school student could be a new testing accommodation. To help the student practice advocating for themselves, teachers may need to remind them of their accommodation and provide prompts for when they ought to use it. The objective would be for them to be able to request this accommodation independently.

Maintaining consistency across school years and school buildings is challenging. Each year presents new staff, new curriculum, new policies, etc. Following through across school years becomes much more doable when a school and district’s administration shares the vision of student-led IEPs and offers its support to the IEP team. Use professional development days or those monthly/quarterly “sacred meeting” times to check in with yourself about the action items and the student’s follow‑through.

What’s Next?

In our fourth and final article in the student leadership series, Self-Determination, we talk about what motivates students and why it is so important to encourage autonomy in your classroom. We review the theory of self-determination, its application in the special education classroom, and the specific strategies teachers can use during the IEP process to encourage student leadership and self‑advocacy.